Washington Senate’s version of rent stabilization would have limited impact on landlord profiteering

To view interactive charts, open post in browser

On April 10, the Washington State Senate passed HB 1217, the rent stabilization bill that would establish a cap on how much a landlord can raise the rent in a year. Yet, prior to passing the legislation, the senate passed several floor amendments that substantially watered it down and curbed its potential to prevent excessive rent gouging.

Rent stabilization is a form of rent control in which the government prohibits periodic rent increases over a specified amount for a time period. The policy is common and has been implemented in various forms by many countries, cities and subnational regions around the world. Oregon and California have also passed rent stabilization laws in recent years.

The original version of HB 1217 applied a 7% annual cap on most rental units, including mobile homes. That meant that for someone who is renting an apartment for $2,000 a month, their landlord could only raise the rent by $140 a month in a single year. The legislation also contains several measures to improve tenants’ quality of life, such as more time before rent increases during lease renewals and a cap on late fees.

The version of HB 1217 passed by the state house is largely similar to the original proposal. The state senate version makes several pivotal amendments that all but gut the purpose of the legislation in the first place. Before the bill can make it to Gov. Bob Ferguson’s desk, the two chambers will have to reconcile the differences between the two versions. I have summarized the main changes in the table below:

As you can see, there are indeed substantial differences, with the senate version being more lenient to landlords (and thus harsher to renters). But to get a sense of how the legislation would function in practice, let’s look at some real world numbers from the housing market over the past few years.

Post COVID-19 rent gouging and inflation

The COVID-19 pandemic, in all its devastation, serves as an important natural experiment for us to better understand the housing market. What happens if we freeze the economy for more than a year while at the same time massively increasing wealth inequality?

Well at first we saw a downturn in economic activity, as many workers were laid off and forced to stay at home, lowering household consumption. This drove down demand in the housing market, resulting in a dip in rents. The eviction moratorium deprived landlords of their primary tool of coercion to compel payments, leading them to bear significant financial losses.

In 2021 as restrictions were lifted and moratoriums repealed, tenants began moving more once again. Many had also saved up some money while they were staying at home. Landlords were well positioned to exploit this and raised their rents dramatically over the following year. By 2023, most of those savings gains were erased.

The 2021-2022 rent spike was historic, with year-over-year rent increases in Washington peaking at 20% in November 2021, according to data from Apartment List (which is partially based on the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey). This then contributed to the cost of living crisis and spiraling inflation, as can be seen in this chart. In fact, housing costs make up 35% of the CPI-U.

Of course, many factors — such as the flood of billionaire cash into real estate investments, the limited supply of affordable housing and a desire to recoup losses — contributed to landlords raising their rents by so much. Rent stabilization is precisely designed to mitigate these increases.

Could HB 1217 have prevented the 2021-2022 rent gouging?

So would HB 1217 have stopped the precipitous rent increases we saw in the latter half of the pandemic? Perhaps, though the data is not conclusive. Both California and Oregon also saw big rent increases, despite their policies.

In general, landlords have so much power in this country that they can find many ways to circumvent tenant rights, evade rent regulation, find loopholes and otherwise expand their already advantageous position in the housing market. Oftentimes they just break the law, counting on their tenants to not call them out or sue them in court. A large portion of the corporate landlord sector is allegedly using AI tools like RealPage to collude and fix prices.

Renters should be wary about anyone who says rent stabilization will single-handedly solve their problems. It may be too much to say HB 1217 could have prevented the 2021-2022 rent gouging. But it might have at least flattened the curve, spreading out the pain of rent increases over several years or giving renters a little more time to search for cheaper housing options.

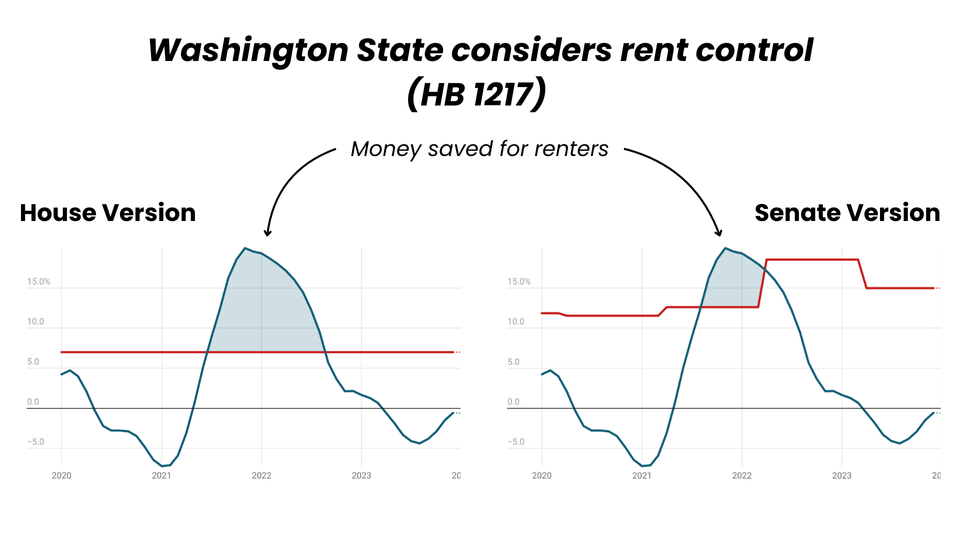

This is where looking at the qualitative differences between the house and senate versions of HB 1217 is important. From July 2021 to August 2022, median rent increases in Washington State remained above 7%. This means more than half of renters could have probably saved a lot of money during that 13-month period of time if the house version of HB 1217 had been in place.

By contrast, the senate version of HB 1217 would have had far less impact during this time, if implemented. Because its annual cap adjusts every year for inflation, it would have allowed annual rent increases of 12.6% in 2021, before jumping up to a cap of 18.5% in April 2022. As can be seen by the charts above and below, the senate version of the bill would have barely made a dent in preventing rent gouging for the majority of Washington renters.

Besides, if a rent control policy allows annual rent increases of 18.5%, what’s the point of having it in the first place? Does going from $2,000 a month to $2,370 a month feel like “stability?”

Of course, it’s not up to journalists like myself to decide housing policy. It is up to Washington State lawmakers, who have until the end of the legislative session on April 27 to hash out the differences between the two versions of HB 1217 and decide if the legislation lives or dies.

This article has been updated to correct the deadline for reconciliation between the two versions of HB 1217, which is April 27.

Member discussion