Seattle joins West Coast cities and Republican states in support of criminalizing homelessness

Author’s note: Thank you for your patience as I took off a week for Passover. Hope you enjoy this post, including the map that took me way too long to make.

Last Monday, the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) heard the case Grants Pass v. Johnson, pertaining to the rights of homeless people to not be criminalized for sleeping outdoors.

Grants Pass is a small city of about 40,000 in Southwest Oregon. Like many other cities and towns on the West Coast, the city has been struggling with a severe shortage of affordable housing. And like many municipalities, Grants Pass has resorted to passing onerous anti-homeless restrictions and camping bans.

According to Street Roots, the city has about 600 homeless residents, but only a single high-barrier permanent shelter with a maximum capacity of 100. Advocates said the anti-homeless ordinances, coupled with the lack of shelter, effectively amounts to a policy of “banishment.”

Under the policy, homeless people are not allowed to sleep in public, whether in a tent, under a blanket or in their vehicle. First-time violations incur a fine, while repeat offenses can result in a misdemeanor and jail time. The law also appears to be enforced in a discriminatory manner — police officers have testified in court saying that they wouldn’t enforce the ordinance against a housed person who was simply camping out to stargaze.

As a result, three unhoused plaintiffs, Gloria Johnson, John Logan and Deborah Blake — who has since passed away — sued Grants Pass in 2018. Both the Federal District and the 9th Circuit courts sided with Johnson and Logan, ruling that the city could not criminalize the status of being homeless. This ruling built off the precedent set in the 2018 case Martin v. Boise, which barred municipalities from criminalizing involuntary homelessness or prohibiting public camping entirely when there is no available shelter.

In 2019, SCOTUS allowed the Martin decision to remain in place, binding governments in the Western U.S. Since then, dozens of other cases have cited the decision, including district courts outside of the 9th Circuit. Judges have further interpreted the ruling to be relatively narrow, allowing cities to enforce “time, place and manner” restrictions on camping while still prohibiting a wholesale ban.

Thus, the core question of Grants Pass is whether homelessness can be interpreted as a class similar to how the 1962 Robinson case prohibited the criminalization of people for being addicted to drugs.

In oral argument, Theane Evangelis, the attorney for Grants Pass argued that sleeping outside is conduct, not a status. Meanwhile, Kelsi Corkran, the lawyer representing Johnson and other unhoused residents, said that having to sleep on the streets is by definition a status. While the three liberal justices asked Evangelis hard-hitting questions, most of the conservative justices, who have a supermajority on the court, seemed sympathetic to Grants Pass’ arguments.

Prior to the SCOTUS’ decision to take on the case cities and states across the country filed briefs asking the justices to take on the case and rollback the Martin precedent. These amicus (or “friend of the court”) briefs offer third parties a way to intervene in an ongoing court case by offering additional information and legal arguments. They can also be a way for those parties to politically position themselves or lobby for a particular outcome.

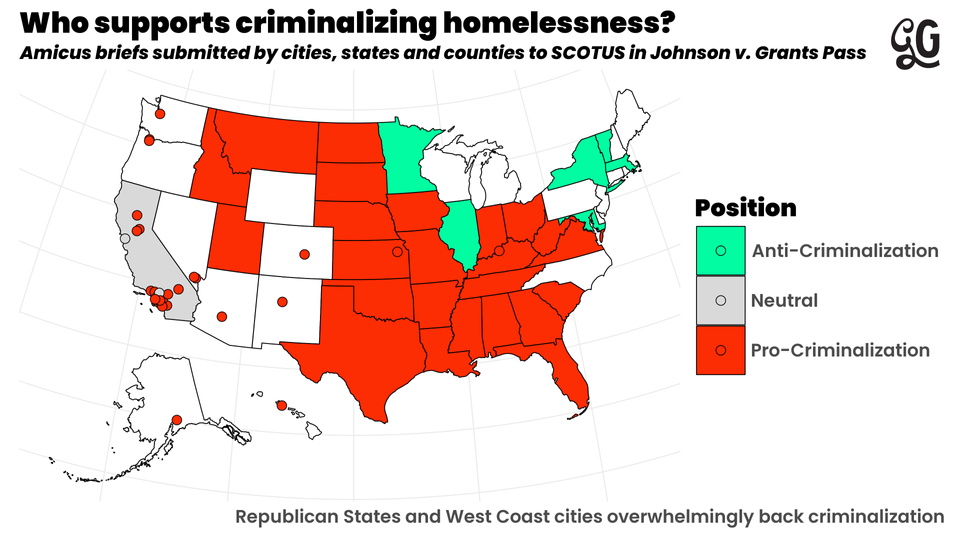

As can be seen in the map, the overwhelming majority of cities and states that have signed onto amicus briefs calling on SCOTUS to rollback Martin and allow cities to enforce sweeping anti-homeless camping bans. This includes Republican Seattle City Attorney Ann Davison, whose office helped write one of these briefs. 24 Republican-led states also filed an amicus brief calling for the overturning of Martin. Intergovernmental organizations representing thousands of municipalities have also signed onto briefs supporting the city of Grants Pass.

San Francisco, Los Angeles and California submitted neutral briefs that argue in favor of maintaining the Martin precedent, but say that some judges have interpreted it too broadly. Similarly, the U.S. Department of Justice has also intervened in a neutral capacity, saying that the case should be sent back to the lower courts and leave Martin intact. Six Democratic-led Midwestern and Northeast states filed an amicus brief siding with Johnson and other unhoused residents.

Non-governmental parties have also filed briefs, with business-aligned groups generally backing Grants Pass and civil society organizations and NGOs siding with Johnson. Balakrishnan Rajagopal, the U.N. Special Rapporteur on the right to adequate housing, also filed an amicus brief supporting the unhoused residents of Grants Pass.

The reason I engaged in this analysis of amicus briefs is because Supreme Court decisions do not happen in a vacuum. Justices consider pressure from a number of different parties and special interest groups. The fact that so many municipalities and states have argued in support of Martin is indicative of a broad consensus among local policy leaders in favor of criminalizing homelessness. If Martin is overturned, we could see cities and states across the country doubling down on sweeps and other policies that punish homeless people.

Member discussion